On 25th February, Future of London held a roundtable with 10 boroughs, two sub-regional housing partnership managers and the GLA on borough-led Social Lettings Agencies (SLAs).

The aims of the session were to discuss the role and potential of existing SLAs, and to debate whether, in view of rising homelessness, the threat of further losses of social housing through central government’s Right to Buy policy and the likelihood of landlords retreating from the sector, sub-regional or pan-London approaches were needed. (As an indication of the increasing prominence of this mechanism, mayoral candidate Sadiq Khan includes the launch of a London-wide social lettings agency in his latest election manifesto.)

This post is a summary of key points from the roundtable; a more detailed briefing is available to the right hand-side of this page.

Not easily defined, borough-led SLAs fulfil a variety of functions, from matching tenants with landlords to varying degrees of property management. Some boroughs are including their Private Sector Leasing scheme (whereby the council leases properties from landlords for several years at a time) as part of their SLA. The defining characteristic is the not-for-profit nature of the work, in comparison with high-street lettings agents.

The majority of boroughs do not see their SLA as directly vying with commercial agents, as they operate exclusively in the sub-prime market, housing vulnerable residents usually in receipt of housing benefit. No boroughs in attendance were operating in the open market, although LB Haringey recently launched Move 51⁰ North to compete with commercial agents.

Most boroughs reported very small numbers of properties being let through their agency; often less than 10, although one outer London borough reported over 100. Even the larger SLAs reported a significant decrease in property numbers over the last 12 months, due to landlords leaving the sub-market.

Most agencies offered cash incentives to landlords up front, in the region of £2,000-£5,000 per property. These big initial costs, coupled with rent around the Local Housing Allowance (LHA) figure, works out cheaper than paying the substantially higher nightly-paid accommodation rates. It was pointed out that financial incentives are the only realistic way of attracting landlords. Most, though not all boroughs, also offered guaranteed rents, sometimes in addition to the incentive payment, or as an alternative product.

In general, borough schemes were falling far short of cost-neutrality. To increase overall viability, one participant proposed broadening the scope of agencies to include market rents, and cross-subsidising the lower-value ones. This was met with some reluctance; currently, practitioners’ chief concern of meeting the urgent needs of their vulnerable residents supersedes the time and planning required to find an alternative financial structure.

London’s gross deficit of properties for temporary accommodation means that boroughs are still outbidding each other. Creating a pan-London agency could remove this competitive element and bring other efficiencies. To be effective, it would need to be built up incrementally, which is difficult for boroughs facing sky-rocketing levels of demand, and with more challenges ahead, such as the lowering of the benefit cap. A valuable – and simpler – interim way to mitigate competition amongst boroughs would be standardising financial incentives and property requirements.The organisations that participated were:

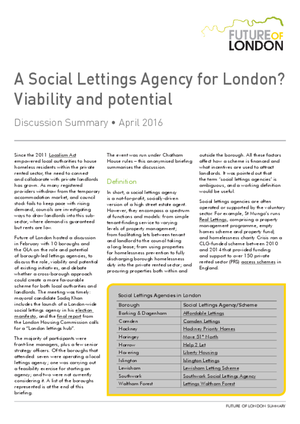

- LB Barking & Dagenham

- LB Camden

- LB Enfield

- LB Hackney

- LB Havering

- LB Islington

- LB Lewisham

- LB Tower Hamlets

- LB Waltham Forest

- City of Westminster

- GLA

25 April 2016